Reports of the death of Sanskrit are highly exaggerated, if for no other reason than the fact that each time the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) returns to power, “the language of the gods” acquires a sudden effulgence. What we see here is an old iteration, a political cycle of eternal return.

The Return of Rama, 17th century manuscript from Mewar

Writing in 1857, the Gujarati poet Dalpatram Dayabhai, marked the demise of Sanskrit with the following poem:

All the feasts and great donations

King Bhoja gave the Brahmans

were obsequies he made on finding

the language of the gods had died.

Seated in state Bajirao performed

its after-death rite with great pomp.

And today, the best of kings across the land

observe its yearly memorial (cited in Pollock 2001: 394).

Historians tell us that Sanskrit died slowly, at different times, and in different places (ibid). But it was also never, strictly speaking, alive: in all the many centuries when it was the language of liturgy and polity, Sanskrit was, demonstrably, a language of the elite. Animated by the concerns of heaven and empire, it continued to possess a degree of creative vitality so that well into the 18th century, intellectuals trained in the Sanskritic tradition were producing texts in a host of genres: language analysis, logic, hermeneutics, science and philosophy (see the ambitious project on Sanskrit Knowledge Systems on the Eve of Colonialism). Today, all we are left with is the “dry sediment of religious hymnology”, a series of moral science aphorisms, and the jingoism of an ethnocentric polity.

BJP leader Sushma Swaraj, who recently called for the Gita to be made the ‘National Book’

And the ‘yearly memorials’ continue to unfold before our eyes… They take shape in Uma Bharati’s suggestion that Sanskrit can replace English in our educational system; in Sushma Swaraj’s contention that the Gītā can be made the ‘national book’; or in the vision of Narendra Modi, standing next to Hugh Jackman in Central Park, concluding his speech with a Sanskrit śloka in an effort to make the language ‘go global’. The Prime Minister today even has a website in Sanskrit: its contents seem to be still under development, but for now it contains a short biography, translations of a few speeches, as well as a series of laudatory quotes in Sanskrit.

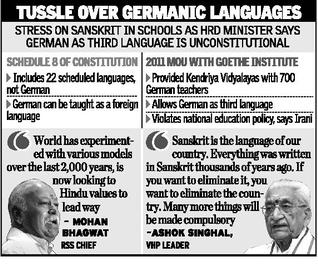

The debates over Sanskrit came to a head recently with the controversy surrounding the wholesale replacement of German as a third-language option with Sanskrit in the Kendriya Vidyalayas (Central Schools). Apart from the understandable uproar that emerged from students at suddenly having to switch languages in the middle of the year, what unfolded was nothing short of absurd. Columns in the media thundered and ranted about the relative superiority (or inferiority) of the two languages. The German Chancellor, Angela Merkel, not only raised the issue when she met the Indian Prime Minister, but went so far as to ask whether the language of her country was being ‘disrespected’ in India. (There seems to be hardly any sense of irony to the fact that the German university system, once a nerve-centre of Indological and Sanskrit studies, has progressively cut funding for these subjects.) Equally without irony was the Indian Minister for Human Resources Development, Smriti Irani, who declaimed that she had taken an oath ‘to abide by the Constitution’, and the continuance of German in the Kendriya Vidyalayas would violate the ‘three-language formula’ contained therein.

In the neo-liberal logic of this day and age, for parties on both sides of the debate, Sanskrit comes to stand for an inward-looking tradition, while German represents a global modernity. This is a false binary if there ever was one, and what gets lost in the noise are certain key questions about India’s educational policy. Consider, for instance, the competing arbitrariness of India’s two major political regimes: the BJP is, after all, only continuing the trend initiated by the Congress, of running educational institutions based on dictat and fiat. Linked to this is the widespread contractualization of teachers, a circumstance which makes it all the more easy to summarily dismiss those whose services are no longer required. And behind it all is the pervasive presence of Dinanath Batra, the RSS ideologue who seems to have become some kind of presiding authority with the right to determine all that can be taught and read.

In the series of totalizing claims being made about Sanskrit, it is described as “the most perfect language ever invented: truly samskrt or civilized” (Srinivasan 2014). The sheer pervasiveness of such claims can be seen in the fact that even one of the judges of the Supreme Court bench before whom the matter of enforcing Sanskrit came up, although critical of the arbitrariness of the measure, proclaimed his support for instruction in Sanskrit. Justice A.R. Dave is reported to have said,

“Why should we forget about our culture? With Sanskrit you can learn other languages easily as it is mother of all languages.” (cited in The Hindu Business Line, November 28, 2014)

Unfortunately, as any historical linguist worth her salt will tell you, the honourable judge’s statement is simply untrue. Sanskrit is not the ‘mother of all languages’. It is not even the mother of all Indian languages. The statement, to the extent that it can be made, is applicable only to the languages of the Indo-Aryan family. This still leaves three entire language families in India — the Dravidian, the Austro-Asiatic and the Sino-Tibetan — which can trace their lineage back to ancestors of equal, if not greater, antiquity. But these languages and their inheritances invariably end up being marginalized in discussions of what frames ‘our culture’.

The case for Sanskrit in the public school system has its basis in the Eighth Schedule. This is a listing in the Constitution which outlines the languages deemed worthy of receiving state patronage and support. Sanskrit was accorded a place in this Schedule as early as 1949. But in many ways this listing was and remains tilted overwhelmingly in favour of the Indo-Aryan and Dravidian languages — and even among them, those deemed to have long antiquity as the bearers of literature and culture. It is only relatively recently, after political mobilizations in their favour, that languages from the tribal belts of India (such as Bodo or Santali) or those that had earlier been deemed uncultured ‘dialects’ (such as Maithili or Konkani) have come to receive a degree of support. Pushed to the margins of political discourse, most of India’s languages are dying a slow death. In contrast, there is the triumphalist march of languages like English and Hindi, spurred on by the forces of nationalism and globalization.

As far as Sanskrit goes, the notion that it is some kind of primaeval inheritance, the fountainhead of all culture, is not a fiction created entirely by the right-wing. Its roots go much deeper, into a cultural world where for centuries the language held a position of preeminence. Such claims for its preeminence continued to be made even in the heyday of the nationalist world. For instance, the Sanskrit Commission, appointed in October 1956, and headed by the eminent linguist Suniti Kumar Chatterji spoke of how “The Indian people and the Indian civilization were born … in the lap of Sanskrit”; it is “in our blood,” the “breath of our nostrils and the light of our eyes” (quoted in Ramaswamy 1999: 345-346). In the minds of many nationalists, the line between ‘Hindu’ and ‘Indian’ had long begun to blur, and Partition only effected a hardening of this divide.

In contrast, at the present juncture, there exist those who would wholly dispense with Sanskrit in any form. They see it as a creature of dead habit, a worthless relic of the past. Watching a recent edition of The Big Picture on Rajya Sabha TV, it was hard not to be infuriated by the disdain with which most panelists spoke of Sanskrit, viewing it through a distorted mirror so that it became solely a vehicle of Hindu grandeur. The left treats Sanskrit as if it were tainted by association, and so does most of the liberal elite. This was not the case earlier — one has only to read the work of D.D. Kosambi, G.P. Deshpande or Ram Vilas Sharma — to see how the Sanskrit tradition was part of their inheritance, even as they wrestled with it and spoke against it.

Sanskrit may be only one of many languages in India’s diverse linguistic spectrum, but it is also a language without which we cannot understand vast swathes of our past. The fact that its defenders today are largely a bigoted lot, is not cause for us to give up the language to them. Instead, we need to view it in all its complexity, as a language that was not confined to the terrain of scripture alone, but one that was also the medium of tremendous literary creativity, the language of abstruse philosophy, ribald poetry, cutting satire and occasionally even trenchant social critique. Amnesia and jingoism cannot be our two cultural choices, for they present us with a version of history that not only shorn of complexity but also quite far from the truth.

Manuscript Cover with Scenes from Kalidasa’s Shakuntala, Nepal, 12th century

The Hindi writer Hazariprasad Dwivedi once wrote of a dream he had, where he saw the Sanskrit poet Kālidāsa standing in front of his house in Shantiniketan and gazing at the flowers of Kanchnar tree. The next morning, as Dwivedi headed out, he paused to look at the tree and saw two figures near it: an art student, drawing the tree in his sketch-pad and a Santal girl who plucked a few flowers from its branches, placing them in her hair before moving on. Meditating upon the significance of his dream, Dwivedi asks, “Kālidāsa kaun hai? Neeche kaagaz par utar lene waala, ya oopar sir par chadha lene vala?” (‘Who is Kālidāsa? The one who takes down [the flowers] on paper, or the one who raises them to her head?) (cited in Sawhney 2004). We lack such an image of the past today: one that is capable of viewing our texts and traditions not as a dead accretion or a vision of mythic splendour, but as a part of the stream of cultural vitality, an accumulation of all the many meanings that make us who we are.